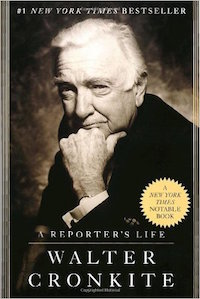

A Reporter’s Life by Walter Cronkite

An enjoyable description of the twentieth century, told through Walter Cronkite’s life experiences as well as his prominent journalistic pieces.

Describing the incidents he reported on as a journalist many years ago, Cronkite also provides his personal opinions, a rarity during his lifelong tenure on the air. Viewing historical events through the lens of an experienced reporter, especially one as renowned as Cronkite for his integrity, provides a fascinating perspective.

Delivering all of the significant world events from the past 24 hours to an audience in a matter of 22 minutes was a daily problem for Cronkite when he anchored the CBS Evening News. He discusses having to balance what events mattered the most to and would have the biggest impact on viewers. It was a balancing act they experienced every day, finding and vetting the handful of stories they would present for 3-5 minutes each. Trying to deliver enough information in those moments to be valuable without turning into a string of soundbites.

This problem resonates with me. I thoroughly enjoy reading various news sources, educational, and informational articles. It could easily take up hours of each day. Meanwhile, I have to balance that with living life. It’s a constant challenge to limit my time consuming news and information versus all the other things I want to or should be doing.

Cronkite expounds on the evolution of news organizations from a culture of objective reporting into infotainment, driven by ratings and advertisement dollars. The number of competitive news organizations declined throughout his career, consolidating into the same parent companies or folding due to failing business models. The competitive dynamic in the early years contributed to the reporters and editors great desire for accuracy, always comparing their stories against their competitors as a means of verification. With that competition dwindling, Cronkite thought the following.

The result is a generation of reporters who have escaped the discipline of accuracy and have left the rest of us with newspapers just a little less reliable, in this regard at least, than they used to be.

Published in 1996, just as the internet was beginning its prolific journey and long before Barack Obama became president, Cronkite’s biography describes scenarios containing many similarities with present day politics. In particular, the current interaction between President Trump and news outlets is eerily similar to the dynamics in post WWII Russia under Stalin and the Nixon administration’s treatment of the press, both of which Cronkite experienced firsthand.

While a foreign correspondent in Russia after World War II, he experienced the impact of government controlled media on the populace. Over a period of months, he describes how his personal driver’s views slowly altered from independent opinions to regurgitating the propaganda published by the communist regime under Stalin. An example of how people can be worn down over time to believe that which they previously knew to be false, purely through repetition and limited access to an independent press.

He had been a driver in the Soviet army and, during our first months together, he spent most of our conversation time praising the American “zheep,” as he called it. To his mind, the jeep was the greatest technical achievement of the twentieth century, and the Americans, in developing it, had proved their technical superiority.

But Alexander was undergoing the brainwashing that the Kremlin propaganda masters had directed to wipe out such impressions left by American aid during the war. The propaganda was vicious and persistent. One of their most heinous lies was that the British and American air forces had deliberately bombed the working-class quarters in Germany in order to rid the nation of those most likely to be sympathetic to the Soviet Union.

I thought surely that the people must find the official claims as ridiculous as I did. But I came to realize how effective lies can be when the truth is suppressed as I heard Alexander’s tune change, day by day. Within months, he was asking me, plaintively and with genuine disappointment, why we Americans claimed to have invented the “zheep” when we knew the Russians had.

During his years as the anchor of CBS Evening News, Cronkite covered the years Nixon held the Oval Office. His description of President Nixon and the administration’s behaviors are obvious to us now, in retrospect, knowing what we do about the Watergate conspiracy. Yet we must remember that it was investigative journalism and the free press that broke open the criminal activity of the 37th President of the United States.

Nixon sat in the White House and thought he had the power to get even with the hated press. So he set his deputies on the job, and Vice President Spiro Agnew was named lead dog…. He identified the network news organizations as the main target in a speech that dripped with vitriol.

The entire attack was predicated on a fundamental belief that there was a press conspiracy against the Nixon administration and all that was right and proper in the conservative world.

This inflammatory attitude towards the independent press has resurfaced in our 45th President, Donald Trump, with his frequent tweets and comments targeting specific news organizations and labeling the press the “enemy of the people.” Using history as our guide, we must think critically and investigate the questions his behavior begs. The independent press must be allowed to continue its job as watchdogs of truth.

Throughout the book, it’s obvious that Cronkite took his objectivity and integrity very seriously during his career. He would rarely provide short editorial pieces, claiming that other reporters, such as Andy Rooney, wrote or performed them with much more panache. Instead, he stuck to what he knew and loved, presenting the facts as he knew them.

My job was to try as hard as I could to remove every trace of opinion from the broadcast. If people knew how I felt on an issue, or thought they could discern from me some ideological position of the Columbia Broadcasting System, I had failed in my mission.